When Peter McGlone asked me to prepare an article summarising the various factors that should be fed into a comprehensive and rigorous energy policy framework I baulked. For this is never how it is done in Tasmania.

Energy policy, more than any other area of policy making, will absolutely define humanity’s collective future. What we do energy-wise has profound implications wherever we care to look: climate change, social inclusion, wilderness harm, traffic congestion, air pollution, poverty, health, business profitability, the state economy, energy security, our trade balance…. you name it.

Yet what purports as energy policy perennially is thrown at us poor citizens like bread crumbs – ebullient headlines evoking shallow parochialism and an absence of any proper analysis: Tasmania to Power the Nation with Pumped-Hydro. It is at this dumbed-down level that energy policy ends up being ‘debated’ in our pubs and across social media and in our parliament.

A sad legacy of this approach is a community that has never been empowered to understand the complexities of energy flows, energy markets and all of the underlying economic, social and environmental implications of decisions. The prevailing community attitude is thus mostly built around pre-existing prejudices.

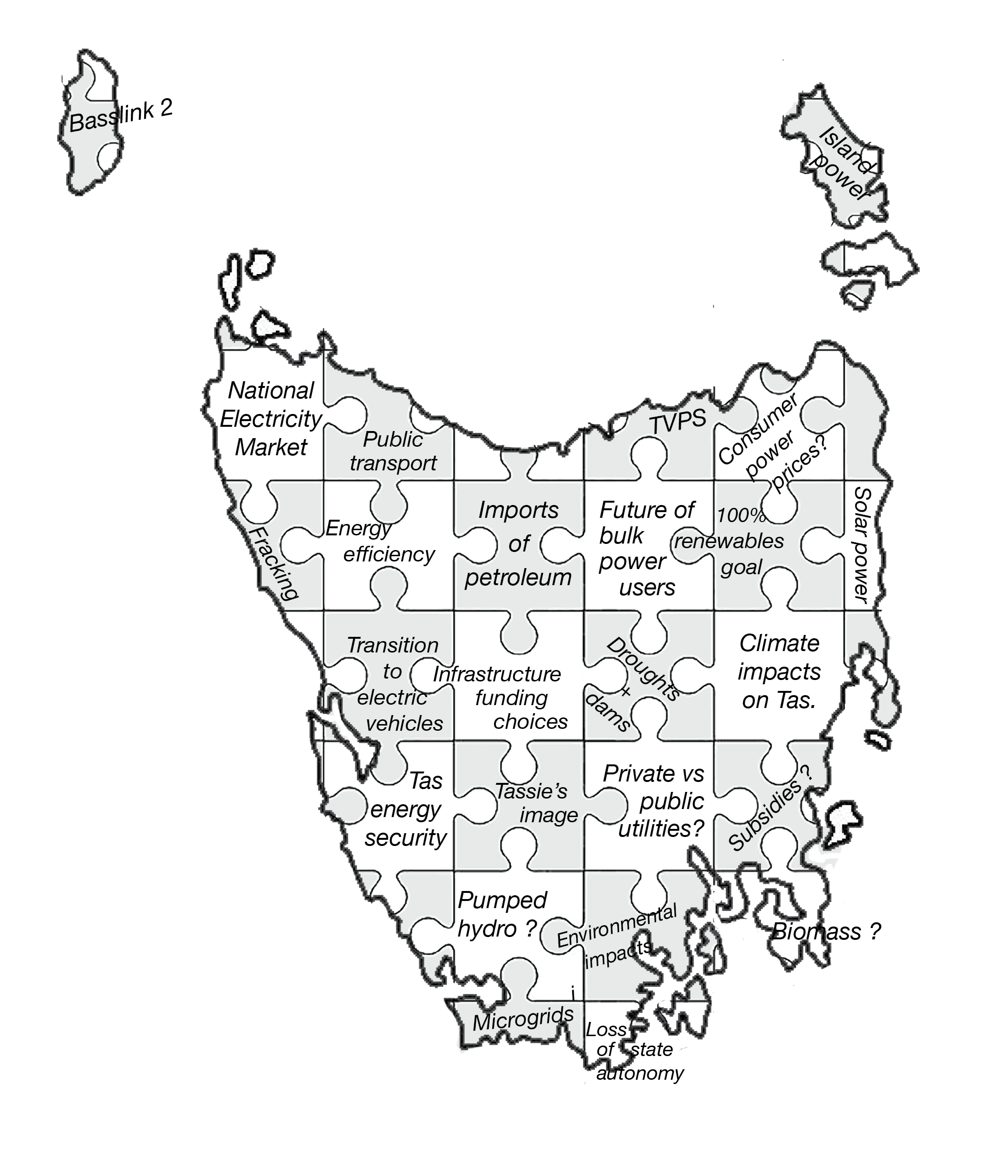

I baulked because each and every factor that we see in the jigsaw deserves a lengthy explanatory essay in its own right in order to do justice to this mother of all issues.

So, below is a very truncated list of some key factors that the Tasmanian community ought to be empowered to come to terms with.

1. Firstly, some hard facts:

Q: How much of Tasmania’s primary energy is supplied by Hydro Tasmania’s hydro-electric system and wind farms?

A: About 35 percent, that’s all.

More than half of our energy usage is supplied from imports of fossil fuels in the form of petroleum products, coal and natural gas. The remainder is made up with wood and some rooftop solar. Tasmania is way, way short of being able to become 100 percent renewable.

Q: What is the cost burden of these fossil fuel imports?

A: For the state, it amounts to some $1.2 billion per year, money draining out of the state economy each and every year. For the householder, the typical Tasmanian family forks out more on their travel energy than they do on their household power bills.

This highlights a problem of perception that’s rife across politics and community: energy is invariably equated to electricity. Yet from climate change, economic and social justice perspectives, liquid fuels policy ought to be the centrepiece of our energy policy matrix.

Q: Can Tasmania hope to achieve 100 percent renewable electricity supply?

A: Yes, absolutely. The state relied entirely on its own power supply until the installation of Basslink in 2007. We now technically supply some 90 percent of our electricity – in an average rainfall year.

The ACT has shown how, through inventive fiscal policy, it is possible to gear up the private sector to deliver local renewable energy supply. Replicated in Tasmania, we would reach a 100% target very easily.

Q: How does Tasmania rank in the transport policy arena?

A: We have the highest per capita car ownership in the nation. Hobart is the only state capital that has no electric pubic transport. Tasmania has the nation’s lowest per capita expenditure on active transport infrastructure.

We need to face up to these facts and use them as starting points to insert transport squarely into the energy equation.

2. Some fork-in-the-road choices that Tasmania should be grappling with:

Basslink: this project linked us to the national electricity market ten years ago – on a pretext of earning revenue from peak power exports. The actuality has seen: 1) a net energy flow from the mainland to Tasmania and 2) some loss of political and energy autonomy. Perhaps more significantly, the ability to import cheap off-peak coal energy has meant that 3) Tasmanian decision makers have declined to forge ahead with viable wind energy projects.

What lessons should be learned from this and to what extent should those lessons guide future energy policy?

Tasmania is financially stuck with Basslink, but it is worth noting that the Australia Institute has recommended that Tasmania consider withdrawing from the National Electricity Market as a means of regaining some level of energy autonomy.

Transport: One thing is certain, electrification of transport fleets is on the cards and will become a significant energy issue within a decade. In Tasmania this could be viewed as a major avenue for improving our energy security, but providing for this transition needs to be planned.

We have a critical choice ahead: whether to focus on building up renewable energy supply in order to: 1) export energy to the mainland OR 2) provide for the power demand that fleet electrification would require. This critical choice should be debated prior to any presumptions about building the mooted second Basslink cable.

Centralisation and privatisation: National energy security has recently become a hot political issue that should inspire a solid debate about what level of centralization and privatization of energy supply is appropriate in our policy settings.

Sustainability advocates have been calling for the development of micro-grids in order to facilitate local energy projects that can’t now happen, whilst the centralized model, chosen by governments, is proving to have major weaknesses in ensuring energy security and price.

Even within the environmental community there is some division on these matters, because successive state administrations have seen these private projects as market competitors to the state owned power utilities. This perception has resulted in private wind farm projects being sidelined, while other viable small-scale projects argue that they suffer from unfair competition through prejudicial tariff arrangements.

Infrastructure funding choices: A decision to invest heavily in a second Basslink (or similar) is a decision that effectively prohibits other investment choices for the state. There is only so much money that Infrastructure Australia awards any state and only so much of GST funds that each state can be allocated. This means that any pork-barreling decision that is requested and agreed to is effectively a decision to rob Peter in order to pay Paul.

There ought to be a first order debate, plus a transparent decision-making process, towards prioritizing what Tasmania’s energy needs and infrastructure funding priorities should be. Insert here any number of energy, urban planning or related infrastructure projects that ought to come under consideration in the energy field.

3. Some ‘trip’ issues that can totally upset the apple cart – i.e. events that would fundamentally upset our present status quo in energy policy.

Security of bulk users: Departure of any one of the big three would radically alter the energy scene.

Petroleum security: Tasmania is at the end of the supply chain and is highly vulnerable in the event of a global security situation.

National climate policy: It’s not inconceivable that a future national government may act decisively and install a carbon price.

4. Diabolical administrative set-up

This one should really head the list of barriers because it is the cause of most befuddlement on state energy matters. At a ministerial level and a departmental level, portfolios of energy and transport are separated to such an extent that there is barely any crossover.

All three incumbent parties in the state parliament tend to maintain this separation, whereby energy policy is almost universally equated and debated within the electricity policy context, leaving the all-important transport sector mostly ignored in an energy policy context (with a tiny focus on electric vehicles).

Even the recent Energy Security Taskforce was asked to report on energy security in relation to electricity supply, barely glancing at security in relation to imported fuels.

5. Iconic projects

Our first port of call as citizens should be to be wary of iconic, pork-barreling projects that are thrown up. Pumped-hydro is the current catch-cry. It has come out of the rather frenzied national energy predicament, with a forlorn hope that the federal government may throw a heap of money at Tasmania. Is it sensible policy?

A major consideration that most commentators don’t touch upon is that being able to supply power, or even peak power, into a market is all very well, but if we can’t bid into the national market on price then the exercise is futile. (This is one lesson that Basslink 1 should have taught us.)

At the end of the day Tasmania has to compete commercially in a market that is dominated by the big three energy corporates (AGL, Origin and Energy Australia). This market is ferociously competitive and – let’s make no bones about this – little Tasmania is a two-bit player.

[For those who want to go into the pumped-hydro option I’ve expanded on it here: http://tasmaniantimes.com/index.php/article/a-pumped-hydro-bonanza-for-tasmania- ]

* * * * *

I’m grateful to Peter for making this call because for the past half century the Tasmanian public has never been genuinely called upon to engage properly on all these multifarious issues so that they can be fed into a sensible energy policy matrix.

It took the Basslink fracture to shake Tasmania’s complacency on the energy front. We still have a window of opportunity to shake down all the pertinent issues before unwise future decisions are made on the run.

The focus should be for all political parties to try to remedy this situation and inform the community how they would conduct meaningful and comprehensive energy consultation and planning into the future.

Article and image by Chris Harries, Climate Tasmania board member.

Dear reader, seeing as you've come this far, you might like to consider making a tax deductible donation to the Tasmanian Conservation Trust. We thank you for your support.