When Australia nominated the Great Barrier Reef and Tasmania’s Southwest Wilderness as World Heritage areas, it was to protect them from damage by specific industrial activities, like oil drilling and damming. Our national environmental legislation includes World Heritage areas and Commonwealth marine parks as ‘triggers’ for the involvement of the Federal government. However, is Federal law equipped to protect these same World Heritage areas from the impacts of climate change?

Australia – a World Heritage ‘early adopter’

In 1974 Australia ratified the World Heritage Convention, incorporating it into domestic law in 1983. Since then Australia has had 16 sites formally recognised as natural world heritage for their outstanding universal value and need for protection. Tasmania’s wilderness world heritage area is the largest conservation reserve in Australia.

Historically, Australia has been strongly committed to the convention compared to other nation states, and recently secured a seat on the 21 member UNESCO World Heritage Committee representing 193 countries that are a party to the convention.

With this seat at the table, Australia is expected to lead by preserving its own sites and upholding the principles of the convention. Failure to do so risks a loss of faith in its leadership and would send a negative message to poorer nations struggling to manage their world heritage sites. The protection of world heritage sites relies on a strong unified approach to uphold the law.

Today, the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (1999) (EPBC Act) is the binding legal and practical link between protecting Australia’s natural world heritage sites and meeting the international obligations of the convention. The EPBC Act is a long and complex piece of legislation, and the realities of climate change present new challenges to its judicial interpretation.

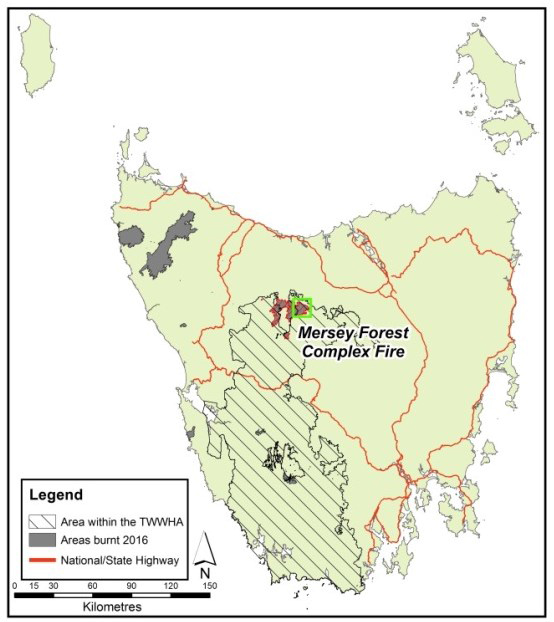

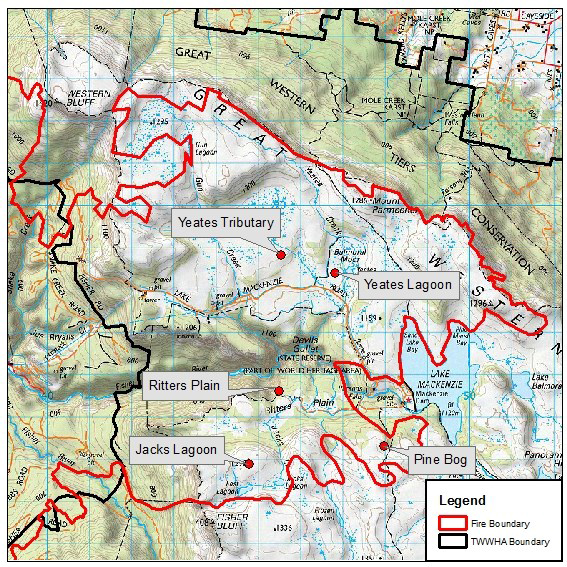

Area of Mersey Forest Complex fires and other 2016 wild fires, with a 1km grid. Maps courtesy of UTAS.

What is happening to the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area (TWWHA)?

In 2017, the Senate inquiry into Tasmania’s bushfire response showed that the harmful effects of climate change are presenting a significant threat to the TWWHA. There is a genuine risk that the ongoing threat of wild fire will one day push the TWWHA onto the UNESCO ‘in danger’ list. Furthermore, with climate change, many ecosystems are starting to change because of increases in temperature, which means wetter vegetation types will no longer act as natural barriers to fire.

In 2016, Tasmania experienced dry lightning strikes that ignited a large number of fires. Eighteen of these affected the TWWHA, burning approximately 19,936 ha (1.3 percent). The Senate inquiry showed that a combination of dry lightning strikes, less rainfall and increases in temperature has caused an increased risk of fire in the TWWHA.

Many of the other threats faced by the TWWHA from climate change are slower and less visible. These include the degradation and loss of alpine environments; increased coastal erosion through rising sea levels; alteration to natural rates of change in the region’s water systems; and changes in the erosive potential of rivers and streams. Over the past decade, there has been a widespread lack of regeneration of fire-sensitive endemic pencil pines. These are some of the longest-living species of tree on the planet. In addition, there has been a decline in the health of eucalypts. Drought and increased temperatures are considered causes. Evidence also indicates that that coastal dune systems are shrinking for the first time in 3,000 years.

Testing the impact of climate change on the EPBC Act

To date there have been a few attempts through the courts to test the EPBC Act’s ability to account for climate impacts on natural world heritage sites - with no success. The most recent case was Australian Conservation Foundation v Minister for Environment (the ACF case) regarding the Adani Coal mine, in the Federal Court.

This Federal Court decision shows the EPBC Act has no clear procedure for considering climate change-related impacts on world heritage areas. A clear and present danger is excessive carbon emissions contributing to repeated marine heatwaves that bleach and kill large sections of the Great Barrier Reef.

A distinct lack of wording on assessing climate impacts within the Act allows an interpretation that can easily dismiss a project’s carbon emissions. The EPBC Act requires a decision maker to address a ‘direct or indirect’ link between an action for approval and the environmental harm it may have on a world heritage site. A major difficulty with this occurs because environmental damage from climate change is often diffuse and incremental, rather than targeted in a specific region or at a specific time.

Challenging a failure to link emissions to individual projects has been historically difficult as evidenced by the Adani decision. The Federal Court upheld the Minister’s decision to disregard local and global emissions and their potential impact on the Great Barrier Reef as reasons not to approve one of the world’s largest coal mines. The emissions from this one mine would make it more likely the world exceeds 2 degrees warming.

How might the Paris Agreement help Tasmania and the TWWHA?

In 2016, Australia announced its ratification of the Paris Climate Agreement. The Agreement aims to keep a global temperature rise this century below 2 degrees Celsius.

Australia has committed to a 2020 emissions target - an ‘unconditional’ 5 to 15 per cent below 2000 emission levels by 2020, plus a ‘conditional’ target of 25 per cent below 2000 emission levels by 2020. Australia has not yet implemented any domestic climate legislation to meet the Paris Agreement. The evidence shows that Australia is on track to miss its first pledged target.

However, Article 7 of the Paris Agreement recognises the importance of all levels of government in controlling climate change. Tasmania has a Climate Change Act 2008 that aims to promote a commitment to action on climate change. This act is mostly soft administrative law, with a focus on an emissions reduction target of 60 percent below 1990 levels by 2050. The act does little to action this target.

But the act could be made stronger. It could be amended to require Ministers and administrative decision makers to consider the climate implications and risks associated with their decisions, to ensure the lowest emissions options are chosen. An independent review of the Tasmanian Climate Change Act in 2017 recommended precisely this approach.

In 2017, Victoria introduced a Climate Change Act that provides a sound model for Tasmania. The Victorian Act embeds a series of policy objectives and guiding principles for decision makers to avoid serious or irreversible damage resulting from climate change.

Such legislation would mean all decisions by the Tasmanian government that result in a net increase of carbon emissions, and therefore impact the TWWHA, would have to be made differently. An amended Climate Change Act would have strong implications for TWWHA management, particularly in the absence of amendments to the EPBC Act. Ultimately the amendments would better align Tasmania with Australia’s international legal commitments on climate change and the World Heritage Convention, and assist Australia’s leadership on the committee.

In a warming world where national governments fail to act, it is the sub-national players like state and local governments that must fill the gap.

Article by Jen Brown - is a Nurse with a Master of Public Health she’s also recent Law graduate, and is passionate about protecting the environment from climate change.

Photos by Mark Horstman.